Brian Hildebrand has been a deeply

dedicated, award-winning, and published

EMS worker (since 1994) and

Paramedic since 2001.

Yes, you read that right.

Since 2001 which included 9/11.

Hildebrand leveled up to become a Paramedic in 2001, so that’s 25 years, next year.

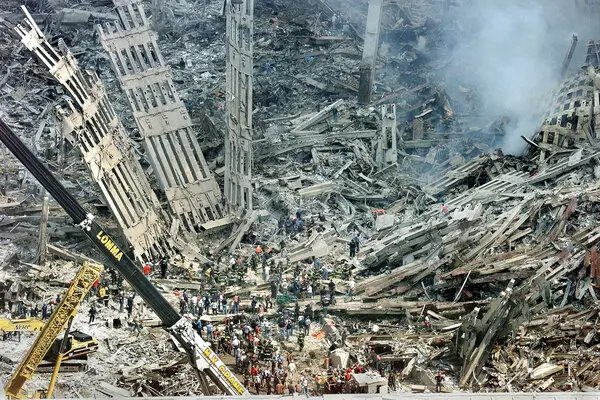

Brian was there @9/11:

Ground Zero, chaos, explosions, dead bodies, toxic debris, fire fighting, survivors, food and water, TV news media and he was there, on-site, on a day we should never forget.

Brian’s idea is to reform the entire healthcare industry from the ground up. To build a system for a more cohesive force.

He’ll settle with a head start by helping his fellow workers in EMS First.

EMS is nicknamed “The Third Service” after the 1. Police Department, 2. Fire Department,

respectively.

EMS workers also fall to #3 on the food chain in hospitals and emergency rooms after 1. Doctors (MDs) and 2. Nurses (RN, NPs).

As the name “Emergency Medical Services” (EMS) suggests, they specialize in emergencies.

So this also means when a police officer, firefighter, doctor or nurse might step into panic mode, depending on where they are mentally, energetically, and physically, an EMS/Paramedic worker does this daily, during every shift and every single day of work.

Someone has a few seconds to live or die, EMS are there. Someone can’t breathe or is choking, EMS are there and saving lives day in and day out.

As part of his personal mission Brian and a few great EMS/Paramedics from across the nation have put together EMS First.

[ EMS First was first envisioned in SI. ]

EMS First is the first organization of its kind in the country. They’re primary objective is to organize and systemize the EMS workers from across the US much like Police and Fire Departments are but better and tighter.

EMS First needs to change some

Brian Hildebrand

of the awful numbers happening

in the EMS industry:

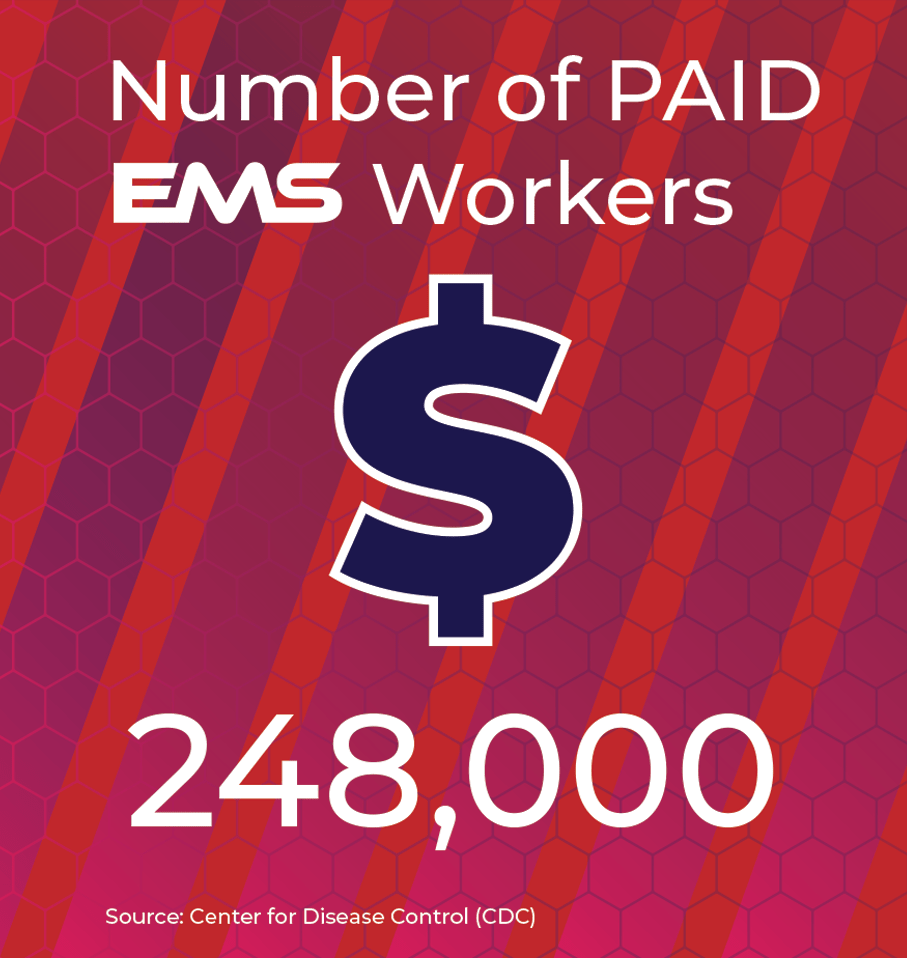

EMS workers face alarmingly high suicide rates and short career longevity, with several studies confirming both trends across the United States. Suicide risk among EMS professionals is substantially greater compared to the general population.

Burnout contributes significantly to early departure

from the field. [pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov]

Suicide Rates among EMS Workers

- EMS providers have suicide rates ranging

from 17.2 to 30.5 per 100,000, compared to

13.0 per 100,000 in the general population.

[cism.utah.gov] - EMTs specifically are 1.39 times more likely to

die by suicide than the general public, with a

crude mortality odds ratio (MOR) of 2.43 in

some studies. [pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov] - Surveys indicate that 37% of U.S. EMTs and

paramedics have contemplated suicide, and

approximately 6.6% have attempted it.

[cssrs.columbia.edu] - Firefighters and EMTs both show elevated

proportionate mortality ratios for suicide,

particularly in older age groups.

[pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov] - Burnout and compassion fatigue contribute

heavily: 73% of EMS providers nationwide

report experiencing it, leading to mental

health risks including suicide. [nysenate.gov]

Longevity in the EMS Profession

- EMS workforce longevity is notably short,

with high annual turnover and frequent burnout. - Up to 37% of EMS providers plan to leave the

field within five years. [nysenate.gov] - Key risks for leaving include frequent sickness

absence (10 or more days nearly doubles odds

of leaving) and planning to leave EMS within

the next year (odds ratio 2.85). [naemsp.org] - National surveys show EMS burnout levels

at 52% in personal domains and 49% in work-

related domains. [sciencedirect.com] - The emotional toll, combined with stressful

working conditions and lack of agency support,

is strongly linked to turnover. [nysenate.gov]

Risk Factors and Protective Strategies

- EMS workers have higher rates of PTSD and

alcohol abuse—PTSD prevalence rates are up

to eight times higher, and alcohol abuse is five

times greater compared to the general

population. [cism.utah.gov] - Chronic sleep deprivation, exposure to traumatic

events, and frequent access to lethal means

(such as firearms) contribute to increased risk.

[pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov] - Agencies can help by fostering a supportive culture,

participatory work environments, and providing

adequate mental health resources—these measures

are considered protective against burnout and suicide.

[naemsp.org]

Overall, the statistics underscore the urgent need

for systemic changes in the EMS workplace to address

both mental health and retention.

Enter EMS First.

#stayalive

————————————————————

EMS: What You Shouldn’t Know

EMS: What You Shouldn’t Know

They say the city never sleeps, but that’s bullshit. The city sleeps plenty—on hard park benches, in crowded waiting rooms, and in the back of ambulances that smell like blood and sweat. It’s those of us in EMS that invariably keep a watchful eye. We run twenty-four hours a day on diesel fumes, caffeine, and adrenaline that is at best half memory and half muscle twitch. I’ve been doing this long enough to recognize my city’s chaotic rhythm by sound alone. The reverberating pitch of a siren bouncing off of glass and brick actually tells you if it’s an ambulance, a fire truck or a police response. Brooklyn echoes lazily, like a low hum rolling through alleys. The Bronx bites, sharp and fast. Manhattan’s noise hits you square in the chest and keeps vibrating there. On Staten Island, you can hear both the direction and the distance. Every borough sings a different verse of the same goddamn song.

You start every shift without variation, the ritual that’s supposed to ward off the chaos. Burnt coffee so strong it tastes like radiator fluid, vehicle check, narc box count, bullshit banter. Someone always says, “Another day in paradise,” and someone else mutters, “Yeah, paradise with vomit.” We laugh because that’s the only way to start a day knowing you might have someone’s last breath under your hands. We are there because we care but dealing with people’s worst time of their life can be trying. You can tell who’s new by the way they wipe the stretcher down, like it actually matters. The rest of us stopped pretending it would stay clean years ago. You keep the motions because the motions are what keeps you sane-ish and keep you helping others.

The rookies still believe the siren means something noble. They think we’re knights with trauma shears, saving the day one patient at a time. They haven’t learned yet that the siren mostly means you’re late for your next job, one among many. Give it a few months and the sound will start to grind down whatever illusions they walked in with. Your purpose for doing the job will be heavily tried. Over time the siren’s pitch gets into your blood, vibrates there until silence feels utterly wrong.

I started in the privates, like almost everyone. Roach-infested garages in Brooklyn; trucks held together with duct tape and prayer, dispatchers who’d sell their own mothers for an insurance card. The bosses had names that sounded like they belonged in a bad mob flick—Charlie Ambulance, Mr Z., Angry Tony. They always had a story about how they “started with one truck and a dream.” The dream usually involved running drugs under the guise of an “emergency service”, Medicaid fraud, and paychecks that bounced higher than the rigs’ suspensions. You’d work sixteen hours straight, grab a slice of pizza, and come back for another twelve because you needed the overtime just to make rent on an apartment you barely slept in.

This was the baptism by fire. No support, no hard and true rules, no mental-health talks, and your mentor was a grizzled lifer who taught through sarcasm and threats. You learned to adapt and improvise, or you floundered. Responding to the first lights and sirens job I ever had, my dinosaur partner lit up a spliff. He looked at me and asked if I wanted a hit. I was a terrified 19-year-old kid and all I could do was giggle, “no thanks”. WTH! I attempted to act like a professional at the “emergency” as my partner gleefully gave me orders. There was nowhere to seek help about the things I saw or even had to do, no one to talk to about my fears, and no one to ask if I was okay. The unspoken rule was you laugh; eat, smoke a cigarette, and you go again. Soul crushing.

Those early years taught me indifference dressed up as professionalism. We were the utter bottom of the heap in both healthcare and as first responders. You learned not to ask too many questions you didn’t want answered, and not to care too much. Caring makes you sluggish which can get you hurt—or worse, unemployed. The hustle was the point. We’d pick up anything with a pulse and an insurance card. Sometimes 2-3 patients at a time. You saw every kind of human misery stacked three high in the back of the boo-boo bus. Crackheads who treated us like Uber, old ladies who called because their cats looked sad, cardiac arrests rerouted because the dialysis run paid better. You learn quickly that EMS in the private sector is about billables, not saves.

In time I moved into the hospital-based 911 EMS system, I thought I was leveling up. New rigs, better pay, clean uniforms, cafeteria discounts, fancy badges. Turned out it was the same grind with better lighting. Now you are a courier with a stethoscope, moving bodies so the hospital’s metrics look good. The ambulance was a moving billboard used to steer patients to your hospital because that was your purpose. Transporting human vegetables was a means to an end. We called it “human recycling.” Every hallway was lined with stretchers, nurses sprinting, and alarms singing. You don’t even flinch when a patient codes mid-transport; you just start compressions, call it in, and keep moving. Even with all of this the desire to help and do right by others remained.

FYI, hospitals are kingdoms built upon quiet despair. Doctors float like royalty; nurses fight like infantry, and we—the medics—are the ghosts who slip between. Not quite staff, not quite outsiders, always blamed when something goes sideways. We are the glue that holds the chaos together, but nobody ever notices the glue ‘till it cracked.

Then came 9/11.

I was just off a 12am – 8am overnight, when the first plane hit.

by Brian Hildebrand

Brian Hildebrand

Email : Info@ICU.house

Web : ICU.house